My interest in electrical engineering started in high school, the day our family computer died — RIP. Up until this point I had designed some websites, written some code, built some computers. I thought my future was in web development and database management. Lame geek stuff. I opened up the computer, thinking I could fix it (I couldn’t) and inspected every board up and down. I was hooked, completely fascinated. Every night after school for hours, I stared at each board and thought: how in God’s name do these pieces of metal on this big green card make stuff show up on a screen?

So I went to school in hopes of learning how computers work. I learned what a modern computer is from the atomic scale all the way up to the programs that let you browse funny cat videos, and I’m gonna deliver a 4 year undergraduate degree to you right now. I am going to attempt to explain every level of it, with just a single paragraph for each level. If you’re completely unfamiliar with electricity, there’s only two terms you need to know: voltage and current. If you think of a circuit as a system of pipes with water going through, voltage is like pressure and is measured in volts, and current is the amount of water going through and is measured in amperes (or amps for short). A showerhead is like a circuit with high voltage but low current, while a river or waterfall is like low voltage but high current. When you multiply voltage and current you get power, measured in watts. With that out of the way:

We start with a humble crystal of silicon. Silicon is one of the most abundant and easily found elements on the planet. Where? Sand! Sand is composed of quartz, also known as silicon-dioxide. That’s right, the technology powering the digital revolution is in a way just really fancy sand! Electric current flows well through conductors like copper, and not at all through insulators like rubber, but it *sort* of flows through a group of materials called semiconductors. Silicon is such an element. Pure silicon by itself is really nothing special, but we can add things like Phosphorous or Boron in a process called “doping” to give it some interesting properties.

Think about switching a light on and off. You have to walk over and physically flip a switch. Thats because the wires and bulbs are all conductors, and the only way to change if power goes through them is physically turning a switch on and off. But with semiconductors you can change whether its a conductor or insulator simply by applying the right voltage in the right way. In other words, you can control electricity with electricity! The general term for devices where a voltage on one terminal lets current flow through the other two terminals is a transistor (short for transresistor).

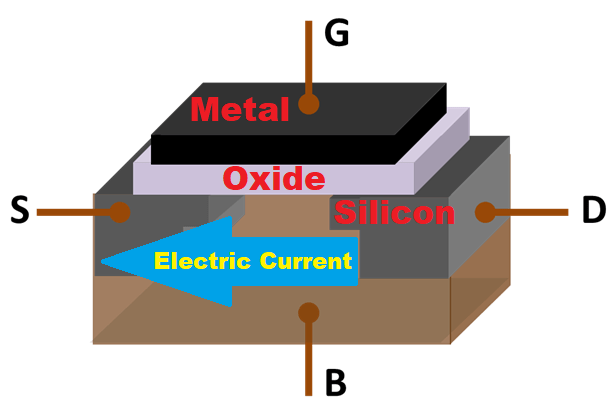

While many types of transistors (and vacuum tubes before that) were used to create computing devices, the key breakthrough technology is this neat silicon configuration invented in 1959 in Bell Labs by Mohammed Atalla and Dawon Kahng called a MOSFET, which stands for Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Field Effect Transistor. That’s a long name but we can break it down into pieces. Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor refers to the “sandwich” of materials that the main body of this device is made of. The metal is a conductor, so we can easily apply a voltage to it. The semiconductor (silicon) is the base that the whole computer chip is made of, and right now it looks like an insulator so no current flows through it. The oxide is a thin insulating layer that separates the two. We apply a voltage, that is to say we push *positive* charges, onto the metal, and that pulls a bunch of electrons up to the top of the silicon, creating an electric Field. Now that there’s a bunch of free electrons, the silicon is a conductor, and current can flow through it horizontally, which is the Effect of the Field. Using our water analogy, this device is basically a pressure controlled valve. But where is that applied voltage coming from? Another MOSFET, which gets its voltage from another MOSFET etc. Its MOSFETs all the way down. Your phone contains millions if not billions of these, so there’s plenty to go around. Modern MOSFETs don’t actually use metal anymore but the name stuck around for simplicity.

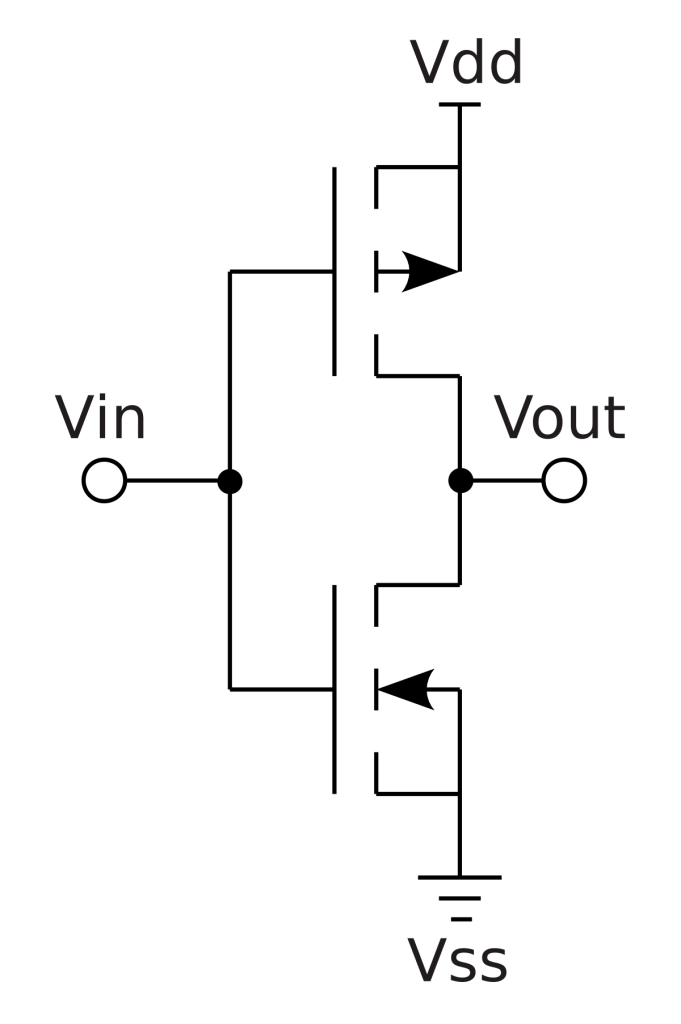

There’s both a negative and positive type of MOSFET, and we combine them together in what is called a CMOS, or Complementary MOS, configuration. This is what CMOS technology is talking about. If we just had one MOSFET, we’d have current constantly flowing and wasting power and generating heat, which we don’t want. By putting a positive and negative MOSFET together, we can turn one on and and one off at the same time. So every time the input voltage switches on or off, one “pipe” is full while the other is empty, and vice versa, creating its own voltage. Why is CMOS technology what enabled the digital revolution compared to other devices? Reasons are many but it’s primarily scalability, power consumption, and ease of use from a circuit design standpoint that’s not important to go into here. #IYKYK

Now we have to take a sidestep into the world of mathematics. Very simple math, don’t worry, the world of Boolean algebra. Boolean algebra (really fun name to say btw) is all about the logic of True vs False statements. It’s stuff like “if A and B are true, then C must be true, but if A is true and B is false, then C cannot be true”. It’s pretty dry stuff. Doesn’t seem terribly useful here though does it? The nice thing about it is that it works on a binary system. True or false, nothing else and nothing in between. Now that word I said, “binary”, you’ve maybe heard it before in reference to computers. Here’s what it means. You know the normal system of decimal numbers written in Arabic numerals, digits from 0 to 9. Once you count past 9, you reset the first digit to 0, and the second digit goes from (an unwritten) 0 to a 1 and we get 10. Neat! Why 10 digits? Well because that’s how many fingers we have to count things with (do you think chimpanzees would count in base 20 using their toes?). This is why the word digits also means fingers. The ancient Babylonians used to count in base 12 because it was very easy to divide and multiply without accurate equipment, and the ancient Romans counted in base whatever-the-hell-we-feel-like. But we can also do math in a base 2 system, where our only digits are 0 and 1, and *all* the math is exactly the same. Nothing has fundamentally changed, you can still do complex calculus and trig, it’s just that the numbers look different. Now we have 0 and 1. False and True. Off and On. We can take our earlier statement and say “if A = 1 AND B = 1, then C = 1”. We can use Boolean algebra to do simple arithmetic.

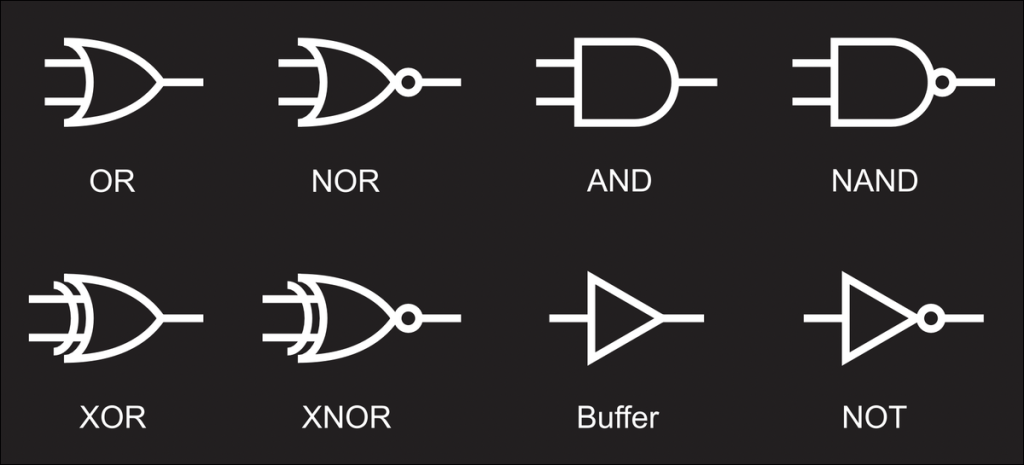

Here’s where we begin to marry our earlier electronic ideas together with our new logical math ideas. This is where the magic truly happens. Voltages can normally be a whole range of values. Like a temperature sensor might put out a voltage of 1V if it’s 70 degrees, and 1.2V if it’s 90 degrees. The temperature and voltage are directly related across the spectrum, as if they are *analogous* to each other, which is why we call this *analog*. But we can also restrict our voltages to just two voltages, to a binary of, say, 0V and 5V. Any voltage closer to 5V we call 5V, and anything closer to 0V we call 0V. 0V, 0, False. 5V, 1, True. We’ve now established how we can create a *digital* voltage system. Let’s bring the actual Boolean algebra back in. Remember the AND section of that earlier equation? That’s what we call a Boolean operator. Takes two logical True-False inputs and produces a logical True-False output. The AND operator produces a True output only when both inputs are True. The OR operator produces a True if either input is True. There’s many other Boolean operators like NAND, NOR, XOR, and XNOR but we don’t need to go over these. You’re just going to have to trust me on this, but engineers figured out a way to use combinations of the digital CMOS to recreate these operators in what are called logic gates. As an example, for an AND gate, if both inputs are 5V (or True, or 1), the output is also 5V.

We have now developed the basic building block of all computers. Many very smartie pants scientists and engineers figured out that by using these logic gates, which they could pretend were taking 0s and 1s, rather than 0V and 5V, and turning them into other 0s and 1s, they could recreate mathematical functions like addition and multiplication on binary numbers exactly like any other numbers. And all this is still with the silicon MOSFET we talked about earlier, the fancy blocks of sand. You have one circuit that just does addition. You have another circuit that just does multiplication. You have another circuit that just takes a number stored in one place and stores it in another place (more on this later). All these different circuits are combined into what is called an Arithmetic Logic Unit, or ALU. This is what is at the heart of every processor. But we don’t *quite* have a computer. Manually entering 1s and 0s would be slower than just doing out calculations by hand at this point.

In comes memory. Im not going to go into detail about physics of memory, because theres multiple technologies, but they all do the same thing which is store the 1s and 0s in an enormous grid. When you see 4GB of memory, that means 4 billion rows. When you see 32-bit that means 32 columns in each row, making it a matrix of 128 billion cells, each holding a voltage that corresponds to 0 or 1. Memory holds two things: data and instructions. Instructions are secret code that go through a decoder. The decoder looks at the instruction and figures out which circuit in the ALU its going to activate. Maybe 011101 is the secret combo that sends numbers to the multiplication circuit. Computer engineers design the logic for these using logic gates from earlier. An instruction is taken from instruction memory and it contains which data memory row (address) to grab, which circuit to put them into, and what to do with the result. It might say “Take the number that’s in address 45, make it negative, and put it into address 87”. Next instruction says “Take the number in address 87 and add it to the number in address 62, put the result in address 405”. And all of this is done entirely by circuits, by a bunch of MOSFETS switching 0V to 5V, back and forth. We have done it. We have a full computer, at least the core. It takes instructions written and loaded in by people, and calculates things and stores them somewhere we can read them out. Sometimes the instruction is to go back up to an earlier instruction, or delete a bunch of old instructions out of memory and load some new ones in. It reads and automatically executes them at a regular timed interval based on a clock (typically on the order of nanoseconds). Technically we could stop here, but this is still a bit abstract isn’t it? We’re still a ways away from sharing memes on Instagram. Scroll back up if you need a refresher because we are now about to go more in depth with those instructions. This is where we move from hardware to software.

Those instructions are what we call code. The giant block of memory containing all the instructions contains several different programs. Up until now it’s all been 0s and 1s decoded by some complex combination of logic gates. But those instructions are *very* simple. So simple that it’s very difficult to write meaningful software. To be clear, teams of engineers went with this route for a while, when you heard “punch cards” they’re talking about feeding long sheets of paper with holes punched corresponding to the 0s and 1s in the instructions. Eventually people got frustrated and created programming languages. A way to convert instructions that are a bunch of 0s and 1s into something readable by humans. The simplest is called “assembly” and is a direct 1-to-1 with the old 0s and 1s. If we know “0110100” means “set this address to all 0s”, why not just write “ZERO” and then the address number? Then another team of people can use a chart to convert the instructions back to the 0s and 1s while leaving the actual software programming to the engineers. Now we can start to think abstractly.

But why stop there? Why manually convert them? Why not write a program that reads the assembly program and automatically converts it? That is an entire class of programs known as “compilers” and has historically been a whole field of study of its own. People then used assembly instructions to create even simpler, more abstract languages that were easier for humans to write programs in, and more powerful compilers to efficiently convert that code. This is a process in technology known as “bootstrapping”. Think about how once we made steel, we could make steel tools, which we used to build better steel-making equipment, which in turn made better steel, and so on and so forth.

What do programs look like? Programs are written in lines of code as described earlier, which are then interpreted by the compiler to output something that pulls all the right levers in the hardware. Numbers go in, numbers come out. It’s a computer, it….computes. Every piece of code is about moving numbers or doing some sort of math with them. Let’s say we want to model a postal worker dropping off mail on a street. Every house is an address in memory (pun intended). The postal worker can just be represented by a number that equals the address they’re on. So if the postal worker’s number equals 72, that means they’re at 72 CPU Lane. This is called a “pointer”. The programmer writes a line saying “check if there’s mail for 72 CPU Lane”. This is known as an “if-then” statement. That instruction is sent off and comes back saying “Yes! There is mail for 72 CPU Lane.” So the programmer then writes a line of code saying “Take the number of pieces of mail for 72 CPU Lane, and add it to however many pieces of mail they already have.” Simple addition. After this is done, it’s time for the postal worker to move on to the next house so the programmer writes “Add 1 to the address you’re looking at” and our postal worker moves on to 73 CPU Lane. The programmer also writes a line of code to say “Repeat this process over and over until you’ve gone through every house on CPU Lane.” This is called a loop function. Almost every line of code ever written is as simple as what we’ve just described. Every program you’ve ever seen from the calculator app on your phone up to the newest Call of Duty is some combination of these basic instructions. This illustrates something crucial to understand about computers: they are very dumb and only understand numbers. A program is nothing but defining numbers or variables, and then moving them around or doing basic arithmetic with them.

To summarize at this point we have a computer made of complex digital circuits made of silicon that can do math based on the programs we write. Time to write some fancier programs! Let’s say we want to write an app where you type in your birthdate and it plays the #1 song of that week. Well hold up there. First we need to write a program to read the keyboard inputs from the touchscreen. Then we need to write a program to actually take the letters you punch and make sense of them. It also needs to show them on the screen. But before we do that, we need to write a program that talks to the screen and tells it how to show different pixels. Plus you need to access the internet to find this so we need to talk to the mobile data chip. And once you have the song you need to write the code to play it over the speakers. This is getting to be way too much for anyone to deal with. Imagine if just to code the most trivial things you had to reinvent the wheel. Thankfully we have what are called “drivers”. That’s right, if you’ve ever tried to fix a problem with your computer and it told you to update the drivers, this is what we’re talking about. A driver is a bunch of code that takes care of the code for all the different pieces of hardware. There’s a driver that deals with the audio card (which itself contains a specialized computer), and now rather than having to rewrite your program for every different audio card, you can just say “hey audio card, play this song from this address in memory!” and the driver does the work for you! Now you can use the same program across many computers, and as long as you have the driver to match the hardware, it’ll work just fine.

We’re almost done here, we’re almost at the web browser level. Before that we hit an impasse. Your ALU, the heart of your processor, can only handle one instruction at a time. When I say instruction I’m talking just one of those rows in your memory, a single “add memory address 5 to address 6 and put it in 7”. But your computer is also worthless unless it can run several programs at once. You’re on your work laptop, and you have 20 tabs open in Chrome, you have MS Word open where you’re writing a report, you have some pdfs open in Adobe, you’re chatting with coworkers on Slack, and you got Spotify open listening to some EDM. All these programs take up millions of instructions that need to happen in rapid succession. How do they all share one very thin resource, one pipeline? When your email client makes a *ding* to alert you there’s a new email while you have music streaming, what dictates which program gets to use the sound? Well, there’s one enormous hulking titan of a program that’s responsible for all the resource sharing needed to make this happen, and it’s usually the biggest piece of software on your computer? Can you guess what it is? That’s right, the Operating System. The Operating System is the head honcho of the software side of a computer. It stands between a piece of software like a video game and the drivers and processor. It decides how files are stored and accessed. And above this level is where the majority of developers create programs. They write programs made for Windows 10, or Mac OS X, or Linux. This is why programs only work with specific operating systems.

This is about where we reach the user level. The level where you, the person reading this, plays games and sends pictures and texts and fills out spreadsheets for work on all sorts of applications. Applications that work the same phone to phone to tablet to laptop. Applications written by programmers coding thousands of lines of software that stream the latest Coen Brothers movie sitting in a server thousands of miles away all the way over to your WiFi router to your Chromecast. Every single one of those devices has drivers, interfacing with computer chips, built up from millions of logic gates made out of transistors doing math with binary voltages delivered by your local power company. And there it is. That’s the full explanation.

Some of you may be wondering about the screen itself. Unfortunately that is a blog post of its own, and I’ll link to it here once I write it up, but the science of capturing images and then displaying them is a work of art.

Welcome to the world of computers. There’s space for everyone 🙂

Enjoyable ad informative! Wish I could read a whole book along these lines, delving deeper and deeper. Thanks for the write up!

LikeLike

Enjoyable and informative. There once was an entire book written in such a manner but I’ve since lost track of it’s title. Might you suggest one? Otherwise, thank you for this!

LikeLike

Loved it !!!

LikeLike