I went back to school part-time to pursue analog integrated circuit (IC) design, and my first class for Fall 2021 was Analog IC Design with CMOS Technology. I’ve added a new page to my list of projects detailing my final project for the class, an instrumentation amplifier for EEG signals. That page goes through the technical details and process and results. I wanted to also provide another side to it, my personal experience, what was going on in my head because boy what a doozy.

To bring everyone up to speed: I got my bachelors for ECE in 2015 from WPI with a focus on computer engineering and DSP. Over time through my career I moved into circuits and PCB design and found a passion for analog electronics. I became frustrated by the fact that a lot of circuit design is just finding the right IC and following the application notes. I decided I would go back to school so I could get inside the IC and get to the silicon where a lot of the real interesting work is. It didn’t make financial sense to go to school full time, so I’d have to work full time and take a class per semester over 4+ years. I wasn’t going to do that at a place I felt unchallenged at, so I started interviewing at places I could do more heavy technical work at that would also be more flexible with my class schedule (anyone from SignalFire reading this, I still love you guys!). So I moved my life to Boston, started school, while finding a new job, all within a couple weeks.

The initial transition was very difficult. For the whole semester I basically never got a chance to relax or breathe. It was like the mental version of living out of boxes; a constant barrage of life events and errands and homework and job interviews all happening at the same time and it took a toll on my health, losing a lot of sleep, and gaining over 20 pounds in 3 months. I told you this would get personal.

With all that, let’s get into the class. The difference between myself and the other students was immediately apparent. Almost everyone was coming in straight from undergraduate except for me and I think only one other person. I was one of very few working at the same time. We held study group sessions at the library where I got to make some friends along the way which I’ll take in a pandemic any time.

The course was *brutal*. Analog IC as a subject is well known for being a difficult subject as it is. There’s so much to wrap your head around in so little time. It’s also known for being very difficult to teach because it relies so much on intuition. You don’t understand that until you try to simulate something in Cadence. Oh and that gets to the other difficulty: Cadence Virtuoso. A chimera of 80 different pieces of software jammed together in the ugliest 1992 UI. It’s impossible to use without explicit step by step instructions.

What’s cool about this is that the black background with dull colors is hard-coded and you literally cannot change it.

I would put the weekly time commitment at roughly 20 hours a week, that’s a fair estimate. When you’re a full time student, you only take two classes, so that’s not too bad. When you’re working a 40 hour job that you’re also starting new and spending extra time every day trying to get up to speed on everything, it pushes the limits of sleep. The barrage was non-stop, just as we were finishing one thing we’d have to start another. Right now I’m taking a semiconductor physics class and it’s pretty much entirely theory. We learn some facts and equations, we solve some problems and answer questions, and that’s about it. With this class, the learning happens pretty entirely from *doing*. If you did the reading, you learned little if anything; you then did the homework, you learned some; but once you simulated and accordingly redesigned one of the homework problems, that’s when you grasped how crazy this subject is.

There was a lot of work but as long as we did the work the grades came through thanks to our professor. The most difficult part about all of it was everything in Cadence. There’s multiple reasons for this. Cadence Virtuoso has a learning curve that rivals Dwarf Fortress. Nothing is where you think it is, and every function feels like you’re opening an entire new piece of software. In fact I’m fairly certain that’s exactly what it is. Everything also just takes a very long time to do. Even if you knew exactly what to put down and knew every parameter, even a simple design would take hours.

Now imagine the actual situation, where you don’t know what to put where, and you can see how you lose track of time. But what if we don’t know what values and parameters to use? We have equations and design methods right? Well, sort of. Here lies the great problem with analog design. The triode-saturation region equations aren’t really true, and there is no real cutoff between regions.

So what ends up happening is you start with a design based on hand calculations, set up your simulations, and then find your gain to be orders of magnitude lower than what it should be. What the hell happened? You have no idea, all you have are these models. The models are not physics based, they’re abstract numerical black-boxes provided by the fab house. Just to figure out the basic things you need for your (not-really-true) equations, like Cox and un, you need to take a single transistor and sweep its terminals and basically create your own Look-Up Table. Then you adjust the W/L ratio for every transistor until things look right.

This part can take hours. Fidget with the ratios. Simulate. Fidget with the ratios. Simulate. Punch table. Etc.

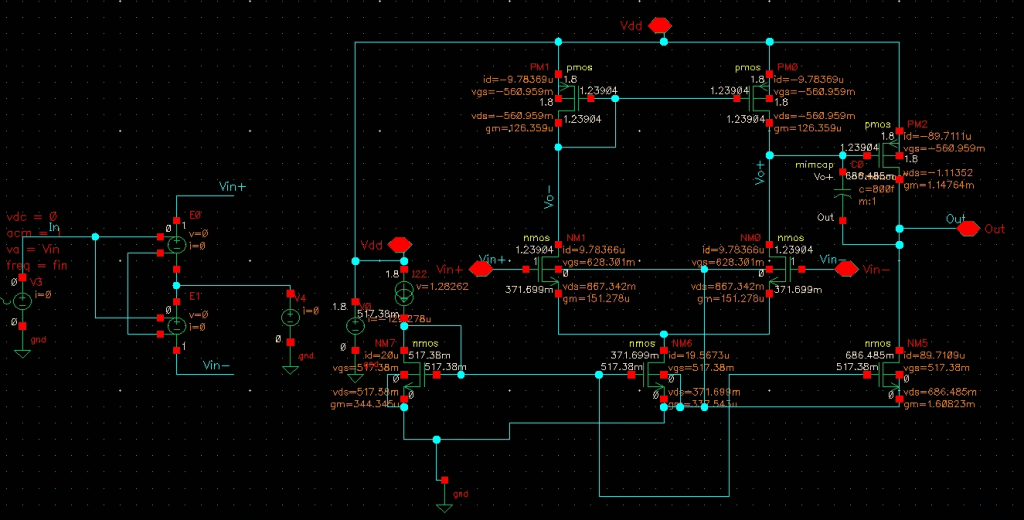

So let’s get to the assigned IC in question. Instrumentation amplifier. You can head to the actual project page to see the technical details and reasons, but long story short we’re trying to build the perfect op-amp, and then once we do that all we gotta do is put the op-amps together in the classic configuration and then we’re good. From there its all layout. With three members, we split it up so I created all the biasing circuitry, my other partner worked on the OTA, and the third, who was from a digital/software background, would handle the report and presentation.

The biasing circuitry took very little time to get right. There just isn’t much you can affect there without a proper bandgap reference, so it was just a current mirror programmed by a resistor. I emailed my completed part to my partner and happily went to bed, not knowing the poor guy was in rapid free fall through the circles of hell.

And make no mistake, designing an op-amp is hell. We went through a few different topologies, each with varying complexity and robustness. The thing is we can’t afford to just “try something out”. Like I said, even if we knew precisely what to do, it takes forever to put the pen to paper, so we felt like we couldn’t afford to waste our work on one topology and spend hours iteratively adjusting and simulating another.

As we felt like we needed to put all our time into this project to finish it on time, my partner got sick. Real sick. I mean went-to-the-ER-and-was-hospitalized-sick, specifically the weekend right before it was due. If he were the one to write this post I imagine there’d be a lot more swearing. Again, thanks to our professor, we got an extension and we did our best to perfect what we could.

Another fun part of analog design is that even if you perfectly design each block, you can’t simply take the output of one block and wire it to the input of another. So even once we built our holy trinity of the op-amp, that is the biasing, the OTA, and the output CS stage, when we put it together it just didn’t work right. Everything has non-idealities, imperfections. And with these, even the slightest imperfection is the difference between an astoundingly elegant piece of technology and a hunk of silicon no more useful than the sand it came from.

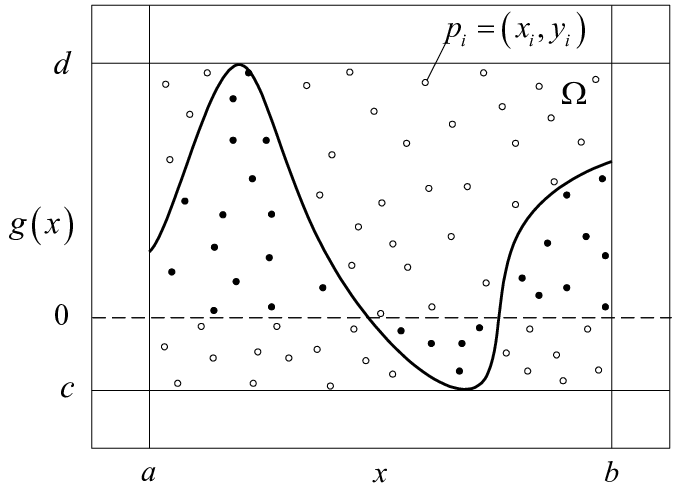

This leads me to what was and probably is for every analog designer the most soul crushing part of the simulations: Monte Carlo analysis. For those unfamiliar, the name itself might remind you of the Monte Carlo casino, and that’s because that’s exactly what it’s referencing. Monte Carlo analysis is about using statistics and probabilities to solve a variety of problems. For example, you can find the area under an arbitrary curve by throwing a bunch of random points on the graph, like darts on a board, and then seeing what percentage of them fall under the curve i.e. numerical integration.

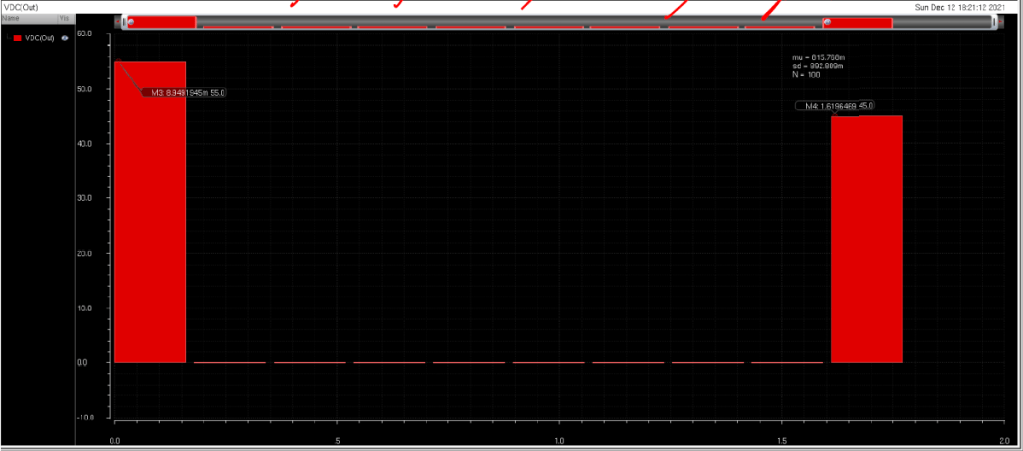

What we do here is run a bunch of simulations, changing certain parameters based on their statistical variance, to see how the circuit will vary in the production process. It is a crucial thing to do, and is a whole world of research in and of itself, there’s many books on making chips and semiconductors process tolerant. It’s also absolutely devastating when you do it right after you’ve nailed the design (or so you think). This was our DC output voltage when the input is 0V.

…..shit. This isn’t even a histogram, it’s just a reverse middle finger.

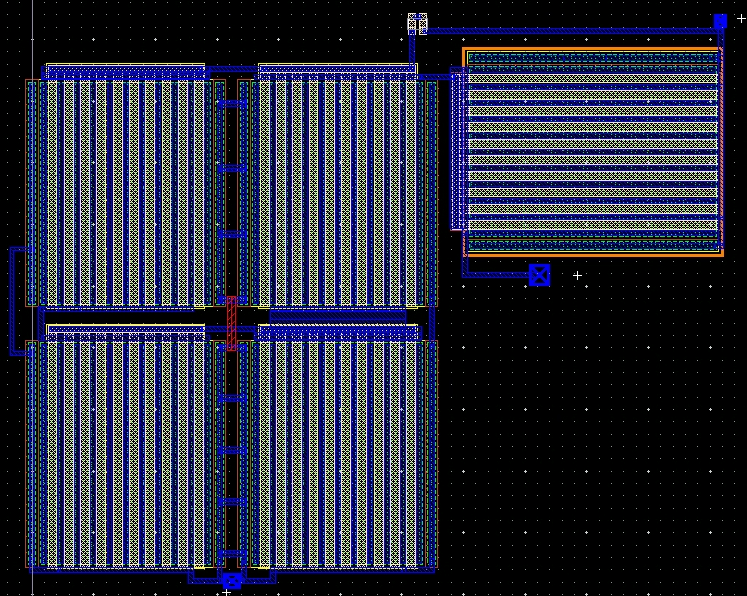

While my partners were still working on the design and the report, I did the actual physical layout. There’s not much I’d like to say about it. It’s not difficult but it just….takes…a very….long….time. And the UI looks like this. Does it hurt to look at? Cool.

After layout, I ran a simulation to extract parasitics and our already terrible performance was further decimated. At this point even with the extension we were completely burnt out. We submitted our paper and PowerPoint at 11:59pm. Couple days later we presented, and you know what? Pretty much every group ended up saying “Yeah we got burnt out and gave up by the end and met like 3 out of 10 specs”. There was something relieving about that.

It felt like a bonding moment. I think we all felt like we had gone through some crazy initiation process. We had no idea what we were getting into at the start. Every one there unanimously said it was the hardest class they had ever taken in college. It was frustrating at the best of times, and existentially destructive at the worst. But you know what? It didn’t turn me off. I felt like I truly accomplished something and I was ready to jump into designing another chip. I was already signed up for a class on mixed-signal IC design 🙂

The night after our presentation I got the best sleep of my life. And then I got Covid 🙂

Greetings from Slovakia, I feel your pain, bro and my deepest condolences to you.

LikeLike