I saw a great question posted the other day, why are high impedance nodes slow? Makes sense why that can be confusing, a transistor looks like a current source, multiply that current by a high impedance that must mean very high gain, why would that not be true at higher frequencies? Why does the resistance make gain high but bandwidth low, it’s just resistance.

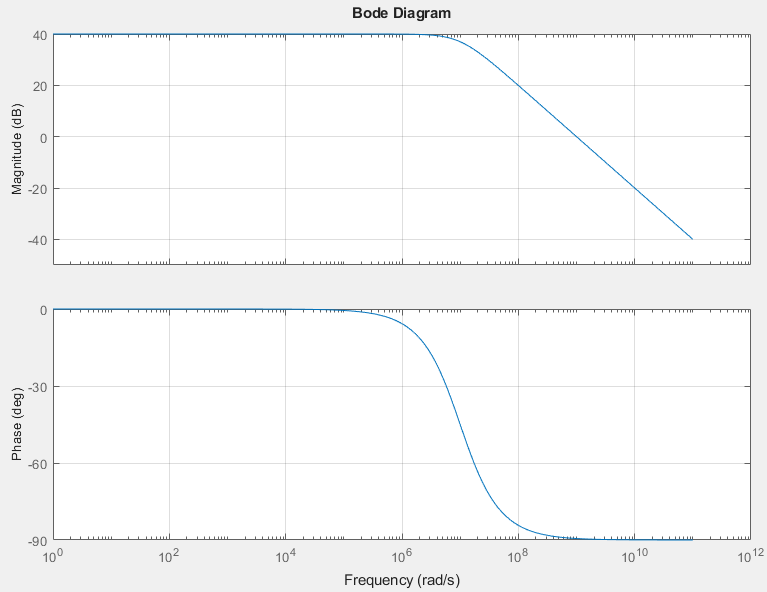

People came in with some great answers from a mathematical perspective, if you solve out the circuit equations you get a pole that is at a lower frequency, so your gain rolls off earlier and can’t amplify high-speed signals and blah blah blah.

I approached it from another angle, which is the physical perspective. Design requires us to abstract the physics to math, which gives us lots of tools to create more complex things, but it doesn’t leave us with good explanations. In the end we’re talking about physical things, metals and dielectrics and semiconductors. “Speed” is not some abstract concept, it is directly about energy transfer.

So from that perspective, rather than asking why high impedance nodes are slow, I’m going to answer why low impedance nodes are fast.

Capacitors, pure and simple

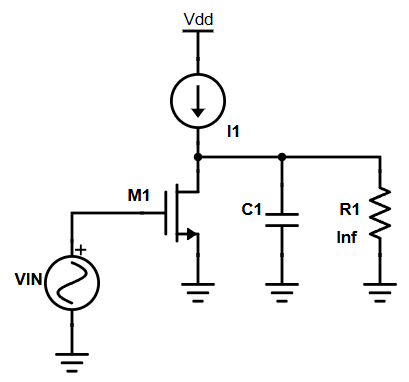

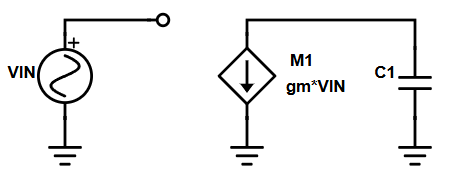

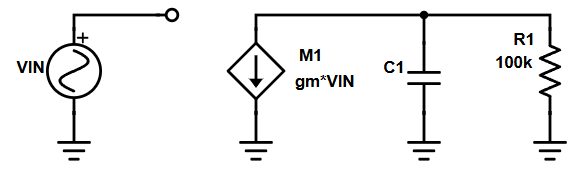

When we think high or low impedance, we normally are focused on the resistance, because that’s usually what we have a greater degree of control over. But let’s step back from resistance first and look at the small signal model of an ideal CS amplifier with a purely capacitive load. This is the extreme case where the output resistance is infinite and thus an open circuit.

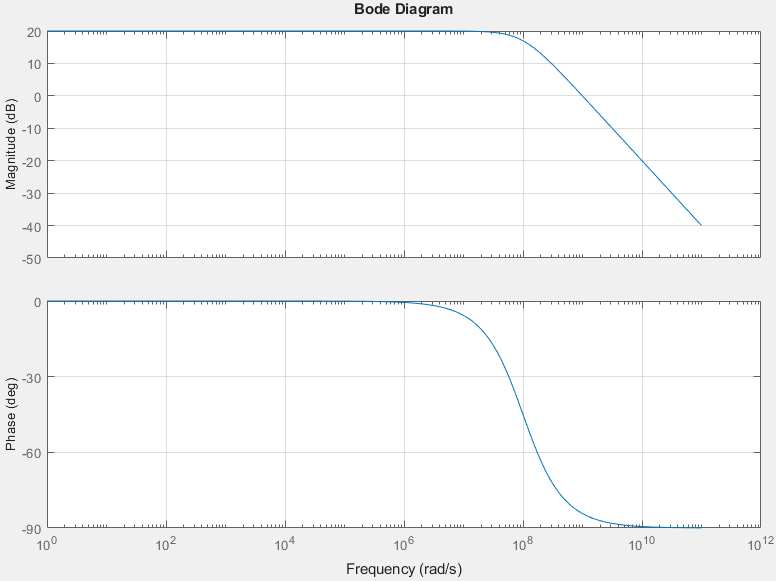

Vin is known, gm is fixed, which means the transistor is supplying a fixed amount of current. In this situation all of that current is directed to the capacitor. At low frequencies, the capacitor is given a long time to charge up and gain voltage. Current translates more directly to voltage and thus we get a very high gain. You can look at the time domain equation even, I = C dV/dt, which means voltage is the integral of current. If your current is a sinusoid, the voltage is a sinusoid of the same amplitude divided by its frequency and capacitance. Small capacitances and low frequencies mean your sinusoidal current translates directly to high voltages. At 1kHz and 1pF, your current to voltage gain is 1,000,000,000! Quite nice right? And the thing is, frequency can get basically infinitely low, 0.01Hz or lower, and gain increases asymptotically.

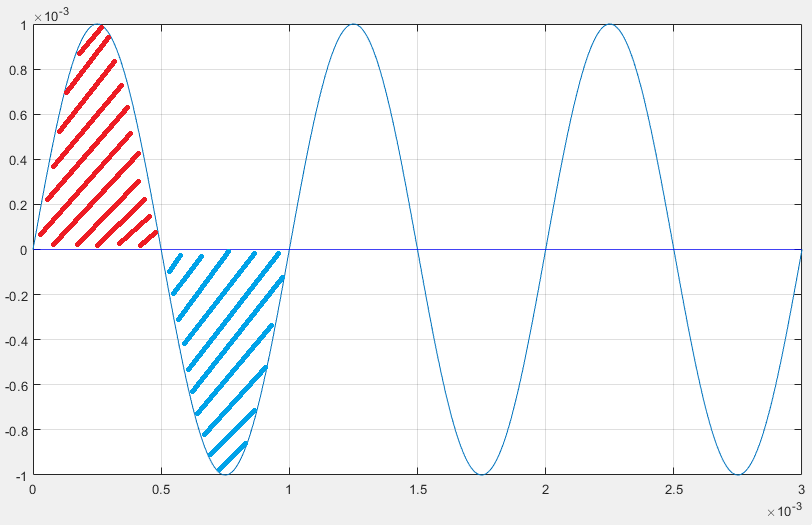

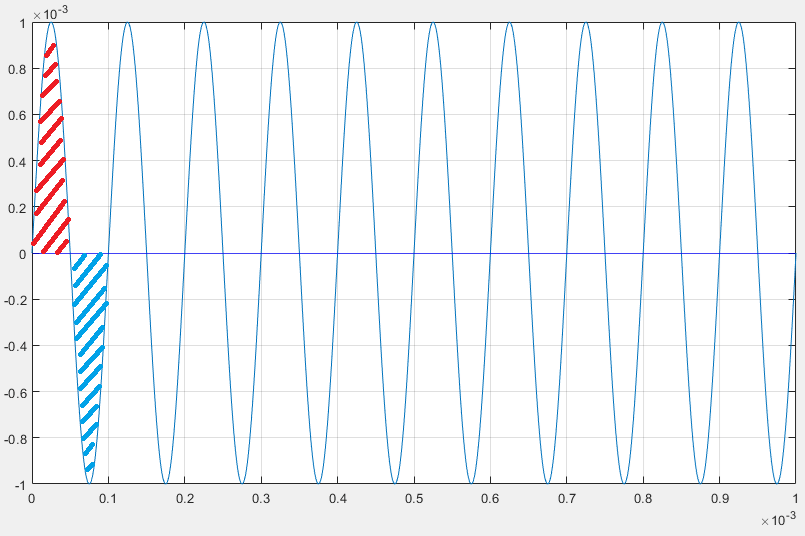

But what happens as your frequency goes up? The capacitive load can’t keep up. It’s still getting charged and discharged, but look at the time domain waveform. At 1kHz, the current was in each cycle (charge/positive vs discharge/negative) for a millisecond, whereas at 10kHz it drops to a hundred microseconds, meaning it has less time to build up charge which translates to less voltage. Same amount of current in a shorter time means less charge which means asymptotically less voltage as frequency increases, by 10MHz it’s basically not producing any voltage. The properties that make a capacitor useful and happy at low frequencies have come back to bite us in the ass at higher frequencies. Such a betrayal 😥 At some frequency the current to voltage gain of the capacitor is exactly the inverse of the voltage to current gain of the transistor. When these two are equal to each other, they cancel each other out and the amplifier can no longer amplify. This frequency is the unity gain bandwidth.

Why are low impedance nodes fast?

Now let’s get to the question. Resistance. Let’s put a 100kOhm resistor there.

Whereas before, all of the current from the transistor was getting dumped into and out of the capacitor, now some small but measurable amount is being lost to the resistor. So at this low frequency, 1kHz, the capacitor still has a current-to-voltage gain of a billion, but now it’s getting less current! Your system now over all provides less gain, but because of this constant resistor, it provides that smaller gain over a wider frequency range. With the pure capacitor, the gain is infinite at DC and 1 at the unity gain bandwidth, here the gain is effectively limited by this constant 100kOhm load. As you go up in frequency, at some point the capacitor and resistor both have the same effect, and above this frequency the capacitor is the “dominant load” and describes the circuit behavior more. This frequency is the pole.

If you bring the resistor down further to 10kOhm, the effect is more pronounced. At low frequencies unfortunately the gain is 10 times lower, the capacitor can’t work its magic since a 10k resistor is siphoning most of the current from the transistor (remember, you have a finite amount of current from the transistor). On the other hand the capacitor’s bad tendencies, how it treats faster signals, doesn’t take effect until much higher frequencies. At 1kHz, the resistor is what defines the gain; it’s less than what the capacitor provides but it’s constant across the spectrum. At 10GHz, the capacitor says “look at me, I’m the captain now”, and acts like a short across the resistor which is powerless to stop it.

So it’s really not that a circuit is “slow” or “fast”, it’s merely responding to whatever inputs it’s given. It’s a result of the fact that capacitors don’t cooperate with higher frequencies, while the parallel resistance determines exactly what “higher frequencies” means. Low impedances stave off those bad habits further up the spectrum, while high impedances are quickly dominated by capacitors’ roll off.