Because I spend all day at work browsing DigiKey and reading articles about electronics, I get served up ads for textbooks, causing me to rapidly and aggressively re-evaluate my life. One of the books it advertised was titled “Wandering Spurs in MASH-Based Fractional-N Frequency Synthesizers” by Dawei Mai & Michael Peter Kennedy.

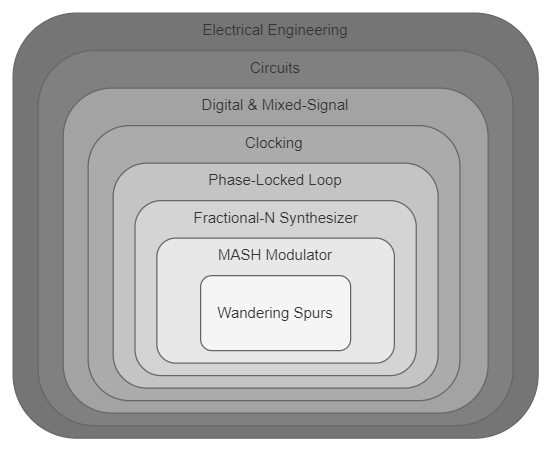

This is the most hilariously specific title I’ve ever seen, while at the same time making perfect sense to me and actually being really interesting. I want to make sense of the title for you, mostly to show newbies and people interested in electrical engineering how wide and deep the field is. There are *so* many roles and disciplines that all look very different, there’s something for everyone.

EE has many subfields, and this falls under the very broad section called circuits. Within circuits there’s power, analog, digital, mixed-signal, and RF/microwave, as well as network theory/simulation on the theoretical side. Circuits can be as large as the transmission lines delivering power from a hydroelectric dam to a factory, or the teeny tiny microelectronics in your wireless earbuds.

We’re narrowing this to digital and mixed-signal (mixed-signal means analog and digital mixed together) circuits at the integrated circuit level. These circuits universally need a clock signal so they can run on time together. Your computer runs millions if not *billions* of calculations every seconds, it depends on decisions being made in unison within tens of *femtoseconds*. That’s a millionth of a billionth of a second, enough time for light to travel less than the width of a human hair. Yeah.

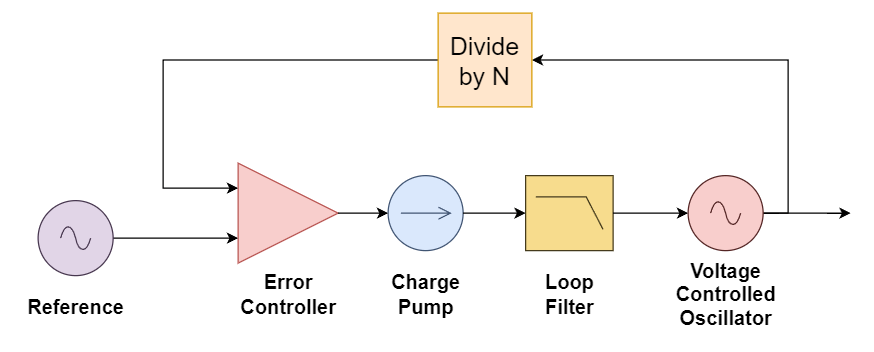

The circuit system used to generate and stabilize the clock is known as a Phase-Locked Loop (PLL). At its most basic representation, a PLL consists of a low frequency but very stable reference (often a crystal), a very high frequency but unstable oscillator, a feedback frequency divider, and an error controller. The “voltage controlled oscillator” (VCO) is crazy fast, it can easily be tens of GHz if you’d like, but is a loose cannon that doesn’t play by the rules. The reference on the other hand is quiet, loves to work steady, measure twice and cut once, but it’ll take its time (literally). By dividing the VCO’s output and feeding it back to the controller, the controller can compare it with the reference and adjust the VCO accordingly, thereby combining the precision of the reference and the speed of the VCO. Feedback is cool.

The divider breaks down into two categories, integer and fractional. Integer-N is when you want the final output to be an integer multiple (N) of the reference, so you can multiply it by 2, 4, 8 etc. This is very common in computer chips. Fractional-N is when you need more flexibility, like in mobile communications where your phone’s frequency is hopping around different channels to get the best signal, so it needs to be able to divide by 124.01 one moment, and then 124.04 the next moment.

Aha! Fractional-N! Finally we’ve reached one of the words in the title! A Fractional-N circuit is something that lets us *synthesize* a clock with a *frequency* of our choice. We’re starting to get somewhere.

An integer-N is relatively simple to make, but fractional-Ns are more complex. Maybe we can divide by 4 and we can divide by 4.2, but what if we wanted to divide by 4.1? Well we can rapidly switch between 4 and 4.2 and average it out over time to get a really precise stable frequency. I’m oversimplifying here but this technique is known as Delta-Sigma Modulation (DSM), more commonly found in data sampling systems like measuring temperature.

There’s a category of DSM blocks called MASH. You wanna know what that stands for? This one’s a doozy. MASH stands for Multi-stAge noiSe sHaping. I wish I were joking. Dumb acronym aside, it means it uses multiple stages of feedback to lower the noise.

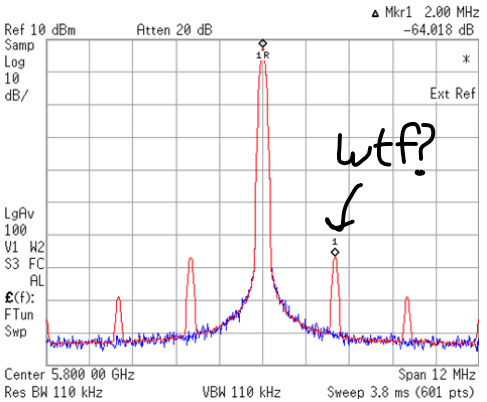

We’re almost done here. Now remember I said we switch rapidly between frequencies and average? In the long run yes it looks like the exact precise fraction we want, but it isn’t actually. We end up with artifacts, frequencies we don’t want. These are known as spurious tones or “spurs”. Most of the time these spurs are fixed, but in many situations, particularly in the kind we’re looking at here, those spurs can slowly shift back and forth in frequency, or “wander”.

And thats it! We’ve successfully deciphered the title of this book. Here’s a graphic showing how deep down the rabbit hole we went.

Now consider how niche this is and yet there’s a whole *book* written about it, with contributions from multiple authors. And there’s still so much more to be written about it, like how to measure it or what effects it might have in specific applications. It just goes to show electronics is a super wide world. Not everything is for everybody, but there’s something for everybody. Could be hands on, in the lab, theoretical, customer facing, anything you want. Each of the blocks in the rabbit hole above has a bunch more categories side to side left untouched. There’s something for everyone but its particularly a bottomless mimosa of discovery for the curious.