Ahhh, ECE 2301, Signals & Systems. There’s something about this class that’s so far removed from everything else. You take a few classes learning Kirchoff’s laws and digital logic and motors and then to fulfill your graduation requirements you take this class where you don’t see a single piece of hardware, a single component, no physics of any kind. I always imagine that in the collapse of civilization, different societies will pop up and they’ll look for electrical engineers to rebuild power systems, and instead they’ll find a bunch of nerds who can write Matlab code.

At some point electrical engineers had to mathematically analyze the signals moving through their circuits. They might also digitize them, and they needed to mathematically analyze that as well. So of course instead of passing that off to mathematicians or computer scientists, they just did it themselves and it took off as an entire field within electrical engineering. Signal processing is at the center of many other fields such as controls and optics, while also becoming a deep discipline in its own right.

One of the most powerful tools in signal processing is the Fourier transform. If you look at a signal in time, it often looks like nonsense. But if you look at it in frequency, you suddenly get some very useful information. Think of it this way, imagine a gym where 10 people are running back and forth, end to end. You look at them and you don’t see much beyond the surface, people are running between two points in a room. But if you measure the time between when each person runs to the end of the room and turns around, you now know how fast each person is running. That’s useful information that you may not have otherwise known just looking at the room of 10 people for a few minutes.

In the same way, looking at the frequencies of an electrical signal can provide us with a lot of novel information about it. When I say “frequencies of a signal”, what does that mean? Well, it can be proven that a signal, any arbitrary signal, can be reconstructed using nothing but sine waves of various frequencies. That alone is amazing and has its own history, but this post will not go into the proof of that and assumes the reader is somewhat familiar with this idea (or can just accept it and move on). Instead, what I’d like to do here is put a magnifying glass on the equation that gives us the frequencies of a signal, the Fourier transform. What I love about it is that while most mathematical formulas are things that are discovered through rigorous proofs and such, this one feels like one that was engineered, as if someone said “I want to pull out the component frequencies and nullify everything else” and designed that way.

Now, when you learn this, you don’t take a function and actually put it in and work it out or anything. You just use tables compiled by much smarter dedicated people and get an output. You sort of have to accept that this equation does what it does, that it converts a signal from “time domain” to “frequency domain”. That if you input a song, you can find the notes and rich timbres. But why? How? How does multiplying a function with an exponential, an exponential with an imaginary value nonetheless, and then integrating it give us a function that means…anything?

First, Euler’s formula. You all know it. When you evaluate it at x = pi, it’s the math version of when Han and Chewie show up in The Force Awakens. All the interesting numbers you hear about are showing up and you can point and go “Oh my god, there they are!”

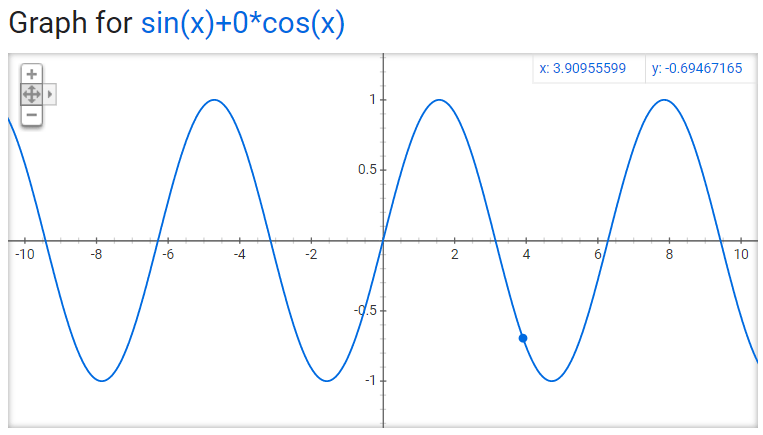

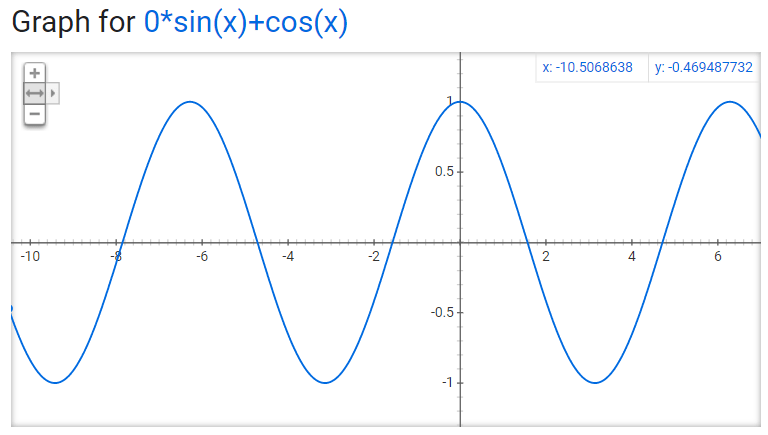

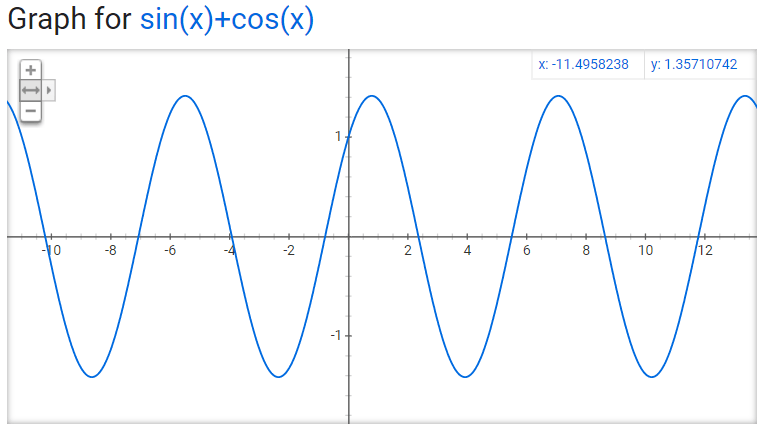

So the exponential in the Fourier transform is really a sinusoid. But hold up, aren’t these…two sinusoids? A cosine and a sine wave. Well here’s something fun, a cosine wave is just a sine wave shifted in phase by 90 degrees. Here’s something even more fun, adding a sine and cosine wave together (each unshifted) gives you a wave with a phase shift somewhere in between 0 and 90 degrees. Don’t believe me? Here lets take a look!

Okay, so this is pretty self-explanatory. A sine wave and a cosine wave. Sine wave starts at 0, cosine wave starts at 1. You’ll notice if you just move the sine wave around you can make it look like a cosine wave. This should be elementary to anyone reading this. Let’s take a look at what a lot of you don’t know though. Let’s see what a wave with a sine and cosine *component* look like. Not just together equally, but with different amounts for each.

Now that’s interesting. The shape of the resulting wave is the same as a pure sine or cosine, but with a new amplitude and phase shift. So we can represent a wave as an amplitude and phase for a single sine or cosine, OR using the amplitudes of a sine and a cosine and adding them together.

With this understood, we can now begin to actually analyze the equation. Let’s say we have a pure sine wave . We’ll give it a frequency of 60Hz, giving us

. We have to multiply by 2 pi because the input is angular frequency, not regular frequency. What we’re after though is

, a function. It might not look like a regular simple input-output function but let’s go ahead and treat it like one anyways. We should be able to pick an arbitrary value for

and get a single output. We’ll choose a frequency of 30Hz, or

, so our equation becomes:

We have two variables, with a function of one variable inside a function of another variable, and it’s an integral, oh god make it stop. Okay okay hold on, don’t run out the door. Let’s take it slow, break it down piece by piece. We’ve set the angular frequency to a single value, so we can treat it like a constant. The integral is with respect to time, not frequency, so really we can just say the frequency is 30 and forget about it. Looking at that right side, time is the only variable left, we know how to handle this.

Something obvious should stand out about the integral of a sine wave. Over a single period, it resolves to 0. Makes sense, right, it swings over the x-axis and then swings an equal amount under the x-axis. You could do this period after period on and on to infinity and it’ll keep going back and forth around 0. The same applies to any similar periodic function, like a square wave switching from 1V to -1V. The product of two sine waves is such a periodic function, so that integral above will just keep resolving to 0 over and over. Khan Academy has a video about integrating the product of two sine waves here: Khan Academy: “Definite Integral of Product of Sines”.

So okay, we integrate the above function, and we know it just keeps going to 0 cause you can see that once again the area above the x-axis is countered by the area below the x-axis from 0 to 2pi. And that’s it, if the input is , the output is

. Well that’s not very interesting. Maybe we just whiffed though? Maybe 30Hz is kind of a shit frequency? How about 45Hz?

Dammit, that’s just going to be the same thing, another periodic function swinging around 0. 180Hz?

This is going nowhere. We keep putting in frequency after frequency and get 0. Is….is the Fourier transform useless? Did I make a mistake in throwing shade at 30Hz? I’m sorry 30Hz, baby please come back. I’m going to try one last frequency before I give up and call Jean-Baptiste Fourier a no-good two-bit lily-livered fraud: 60Hz. There’s a fuckin’ novel idea huh? The resulting graph looks like this:

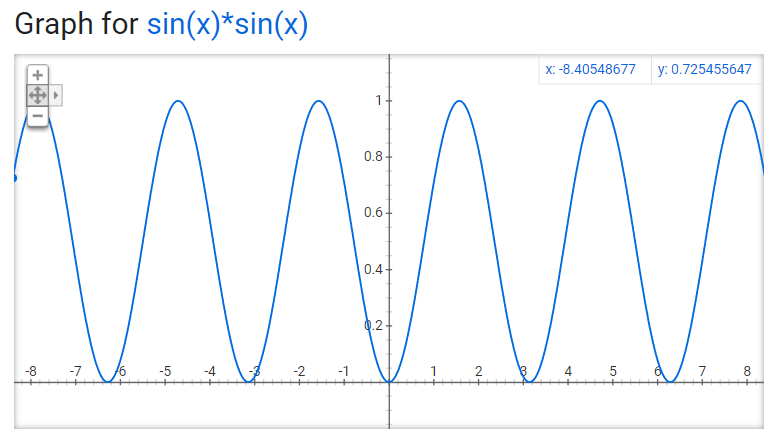

Notice something? For one, it pretty much looks exactly like a regular sine wave, nothing funky. But more importantly, the entire thing is positive, above the x-axis. It makes sense right? Unlike the other products of sine waves, this one is unique because it’s a sine wave multiplied by a sine wave of the same frequency, which makes it a sine wave squared. Squared value, whole thing has to be positive. And when you put that into an integral you get a non-zero value. It’s sort of like it still swings around 0, but raised up a bit. If your input sine wave is shifted in phase, it can be broken into a sine and cosine wave, so you’ll get a sine wave squared plus a cosine wave squared (a sine wave multiplied by a cosine wave just gets you a sine wave with twice the frequency and half the amplitude, so again integrates into oblivion).

Any frequency put into the Fourier transform where f(t) is a pure sine wave will ultimately fail and give you 0 except in the case the frequency matches the frequency of f(t). Do you see where we’re going with this?

We said at the start that any arbitrary f(t) signal is actually made up of several different sine waves. Put that f(t) into the equation above, and it equals 0 for any frequency except those that make up the input signal. And that’s it! We’re done! That’s how the Fourier transform works. I hope that helps de-mystify that spooky looking equation.

One thought on “Fourier Transform: WTF does that equation mean?”